What do we do about stories that are too big for small teams?

The most common solution is to form a large team, grouped into sub-teams by subsystem, layer, or technology.

Then turn too-big stories into two-level stories: an upper-level whole story that makes sense to a user, and lower-level stories organized according to the system structure.

We’ll look at how teams follow this approach, why it makes it hard to deliver, and what to do instead.

Component-Based “Stories”

Suppose a product owner (PO) wants a behavior from the system:

Generically, there’s some Stimulus, which results in the system Response, doing something now or in the future: S → R.

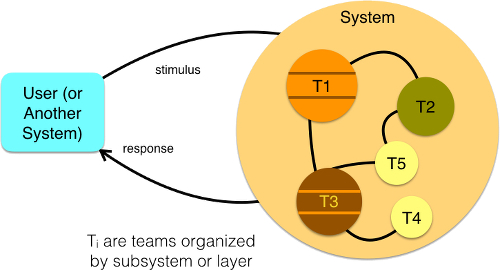

What the product owner may not realize — and certainly doesn’t care about — is that the system is so big it’s built with components and layers:

The challenge comes in organizing work for the large system.

What many teams do is:

- Assign teams to each subsystem or technology

- Assign a PO per subsystem, often a business analyst (BA) or proxy PO

- Split the real user story into “stories” that make sense to those subsystem teams.

The original story:

S → R - User sends the system a Stimulus, resulting in some Response

The split stories: (where Ti are different teams corresponding to the subsystems)

S → T1

T1 → T2 and T3

T2 → T5

T3 → T4

T3 → R

Now, if you add up all those smaller stories, the intent is that they add up to the original S→R story. They might even do that!

But - what value is there in each individual sub-story?

None - no sub-story by itself lets the user accomplish anything.

Our schedule is risky too: we can’t integrate or test until every piece is done.

Signs of Trouble

How can you tell when whole stories have become component-oriented sub-stories?

The biggest clue is the user in the story’s title: If the “user” of a story is a component inside our system, we’ve lost track of the real user and probably do not have a whole story.

The biggest place to be careful is when splitting stories, where it’s very easy to shift the user. For example, if we split User finds matching items into Query Parser parses query, Search API finds matches, and User interface displays matches, we’ve moved into the implementation domain with an internal “user”.

Component-based "stories" use the trappings of stories to let you pretend to deliver incrementally. [Tweet This]

The Consequences

Subsystem product owners aren’t personally attached to “their” sub-stories; they know that these fit into the big picture somehow but it’s not clear why or how one story could be more important than another.

Subsystem POs struggle to make tradeoffs: their “customer” (probably another subsystem) specified what they wanted, so what’s to trade off?

There’s a worse variant I’ve seen at several companies:

An overall plan gets made.

Product owners get assigned at the subsystem level, but there is no overall product owner. (There may be a product manager making high-level decisions, but no single person cares about the overall interactions.) Without customer feedback to guide them, stories languish or get over-engineered.

The original story may eventually pop out of the software factory, but a large batch of atomized pieces reduces the overall team’s focus on delivering capabilities quickly.

Without an advocate for the overall story (behavior), integration is haphazard - and issues are not detected until final testing.

This approach makes it hard to deliver effectively. Instead of a continuous flow of value, we have a lumpy flow. Instead of involving users throughout, we engage them only at the

beginning and the end (increasing the risk that we develop the wrong things). Instead of changing direction because of what we all learn, we cling to plans made at the time of our peak ignorance.

Solution

Move beyond the trap of letting your system design dictate your approach to planning and implementation:

-

Focus the whole team on the product point of view

-

Draw distinctions between stories, tasks, and processes

-

Organize stories at all levels in terms of product capabilities

-

Organize teams to deliver those product capabilities

1. Focus on User Goals and the Whole Product

A product is not just software or features - it’s everything that contributes to the customer’s experience.

Technical tasks do have to happen, but they’re only in service of the overall product.

Keep the team centered on the users’ goals and the capabilities users need.

2. Draw Distinctions Between Stories, Tasks, and Processes

Teams have adopted the notion of user stories when working with Scrum, SAFe, XP, and other processes.

But they’ve often become so used to speaking about stories that they call everything a story:

scenarios involving users, behaviors of internal components, and even steps in the process. The assumption is that if you can fill in the blanks of “As a __, I want to __ so that __”, then it’s a story.

Drawing finer distinctions will improve your thinking and your behavior:

-

User story (or just “story”): Scenarios valued by users, taking an external view of the system. Example: Send an email message.

-

Task: Something we do to implement a story, but doesn’t deliver a complete story by itself. Example: Create a database table.

-

Process step or activity: Actions we take to create and deliver software. Example: Hold a planning meeting.

By using separate terms for these concepts, we help keep concerns in the right domain. For example, by recognizing that “component stories” (ugh) are really “tasks”, we can see that even though our schedule might show us making progress on tasks, we may not be making progress on stories.

3. Organize Stories by Product Capabilities

Keep the focus on true user stories - oriented to a customer value, described in domain terms, and external to the system being developed.

If you’re developing embedded systems for which there is no human user, the “user” may be an external system; that’s fine. But even then, make stories be about interacting with the neighboring systems, not about the internals of the system being developed.

Move away from technical splits based on the system’s structure.

Instead, learn to grow stories rather than split them: Get a minimal version of the story in place, then intensify it: add features, improve qualities.

For example, if you’re creating an email system, sending a message is a key capability. We may have all kinds of features in mind: to/cc/bcc, suggesting recipients, mailing lists, multiple accounts, attachments, spell-checking, etc. Rather than tackle some subset of those all together, simplify it. Perhaps start with one account, “to” addresses only, basic text messages only. Get that working, as close to shipping as you can, then add features one at a time.

Keep in touch with the user to ensure they can see the value. This can help tell you what’s the next most important thing to implement, and you often find that users are ready to use your system even sooner than you expected.

4. Organize Teams to Deliver

There are competing ways to organize work, but many teams don’t consciously choose. We could structure work according to:

-

The architecture of the system being developed (components and layers)

-

The skills of the team (workgroups with similar/related skills)

-

The goals and capabilities of the product (as seen by users)

When we’re delivering at a slow pace (months or years), we can get things done with most any organization.

But as we shorten our cycles, we need to move toward the goal and product view: “What can we do next that will have an impact?” (even if that changes our plans).

Conway’s Law suggests that the design of a system reflects the design of the teams and the communication between them.

That suggests a way out: change the organizational structure.

So: Build teams that are able to pick up any story, with the full set of skills needed to take a capability from start to delivery.

Not only does this make delivery a natural focus, it simplifies planning, and makes clear to the team that broadening and deepening its skills will improve its results.

You don’t have to make this shift all at once; you can start by introducing one or two delivery-focused, cross-functional teams, and grow from there.

Conclusion

If you’re splitting stories for architecturally-oriented sub-teams to deliver in a big batch, you’re missing some key benefits of agility.

Instead, create whole stories for whole teams:

-

Whole stories: They can be small, but must still provide the user some new capability or benefit.

-

Whole teams: They can be small, but must be cross-functional and able to take stories from start to delivery.

Taking this approach will make your plans more flexible and your deliveries more valuable.

Thanks to Chris Freeman, Gerard Meszaros, Curtis Cooley, Tim Ottinger, Arlo Belshee, and Joshua Kerievsky for their feedback on earlier drafts.