Influencing the conversion from cooperation to collaboration

This is a co-authored post with Olivia Vick.

The ability to work with others effectively is even more powerful in 2020, with many meetings occurring remotely. To make up for the loss of in-person interaction, we must be extra attentive to gather the information we would normally get from meeting in person. But even before we were relegated to remote meetings, the importance of working in teams was a popular topic. According to a 2012 McKinsey Global Institute study, 72% of teams are adopting social tools with the goal of achieving the full potential innovation and efficiency through highly collaborative teams.

In our previous post, we discussed external reasons that might make real collaboration a challenge: budgets, time constraints, existing staffing models, legacy paradigms. These are real impediments, but adopting collaboration can be easier than you think. It can also be worth the trouble: collaboration can actually result in faster, less costly project execution as well as happier, more engaged contributors.

Why should we collaborate?

Collaboration – the act of working with another person or group of people to create or produce something –allows for more creativity and can be inherently motivating for contributors. Whereas cooperation is codependent, collaboration is interdependent. The complexity of the objective is another important factor to consider. Because uncertainty increases as complexity increases, collaboration can ensure greater likelihood of success, addressing interdependencies.

“As work becomes more complex, teams are more likely to be engaged in true collaboration. These teams are ambitious, with goals to lead their industry, influence regulations, or improve standards of living.” - Mark Ace, VP Enterprise Services, Leanpath, 2018.

Collaboration may seem less organized, but if everyone shares the same goal and values, the same work gets completed with a more holistic approach and better result. And if collaboration is done correctly, teams will effectively self-organize with inclusion and psychological safety, further reducing the time to accomplish their goal. In contrast to cooperation, key components of collaboration include:

- Leveraging contributor strengths, knowledge bases, and interests as needed. Given that team members may differ between projects (common for matrix organizations); the way that individuals contribute to those projects also needs to differ. This is a flexibility that ultimately allows for higher level connections to be made sooner in a project, mitigating risks and validating assumptions.

- Collective awareness and ownership via more open communication among the entire team, regardless of role, about the status and timeline of a project, with inherent whole team accountability and interdependence as an explicit competitive advantage.

- Shared amalgamation of project progress in relation to product objectives. The ability to have open dialogue in which a team can think collectively on a higher level, meaning decisions have more buy-in and fostering unity accelerates the ability to deliver value.

Collaboration feels better for everyone involved and is based on mutual trust, respect, and inclusivity. It requires everyone to suspend personal politics and facilitates constructive conversations. Not everyone has to agree, or should, but in collaboration each contributor is heard and validated for their points of view. There is also more room for contributors to take on new or different challenges and expand their knowledge. The diversity required by collaboration can bring about ideas that would be impossible without collaboration’s connective thinking. This connective thinking can help identify and abate potential risks earlier in the process and result in a better product design overall. As for business benefit, high-performing businesses are up to 5.5 times more likely to be fostering a collaborative workplace.

Need some more clarification on collaboration?

There isn’t a solid line between cooperation and collaboration; both can occur within the same team or even on a single project. For example, you may have a team that is able to collaborate in one-off situations like an individual meeting, but day-to-day work is task-based and individually focused. These blurred boundaries may fool you and your coworkers into thinking you’re fully collaborating (“Wasn’t this meeting great!?”) when your daily work lacks the same level of collaborative connection, resulting in lower energy and motivation.

One-off collaborative situations do not result in the benefits of consistent collaboration. It is common for functional teams to “hand off” work, in a “serial collaboration” structure that functionalizes collaboration in individual events rather than embracing it as a baseline operating mode.

“One of the biggest mistakes that managers make is trying to foster what we might call “serial collaboration”, i.e. going from one function to the next and trying to cobble together an agreement.” - Ron Ashkenas, HBR, 2015.

Serial collaboration results in rigid prerequisites, especially in component-based teams. Such prerequisites likely need to be revised, but because of the separation and lack of communication inherent to serial collaboration this correction does not happen until later, causing delayed feedback.

Real collaboration can cause delays too, but these delays add clarification and often result in risk mitigation. Collaborative delays are productive delays, which mitigate the reactive and corrective delays of serial collaboration. Real collaboration allows identifying and addressing issues earlier as opposed to facing the long term delays of addressing a problem that arose because of disconnected (and uncollaborative) planning.

Collaboration needs to be correctly fostered and utilized to see the benefits. Recognizing the benefits of collaboration can be challenging, because there are time delays in the process of achieving a collaborative culture. Depending on the industry, it could be well over a year before a business can see the full effects of changing to collaboration. Adopters should note that with this time delay, often the effects of collaboration get attributed to other more operational changes, when they should be attributed to a culture change. If leaders do not recognize the importance of culture then they don’t measure it or prioritize it.

So, how can you influence the conversion from cooperation to collaboration?

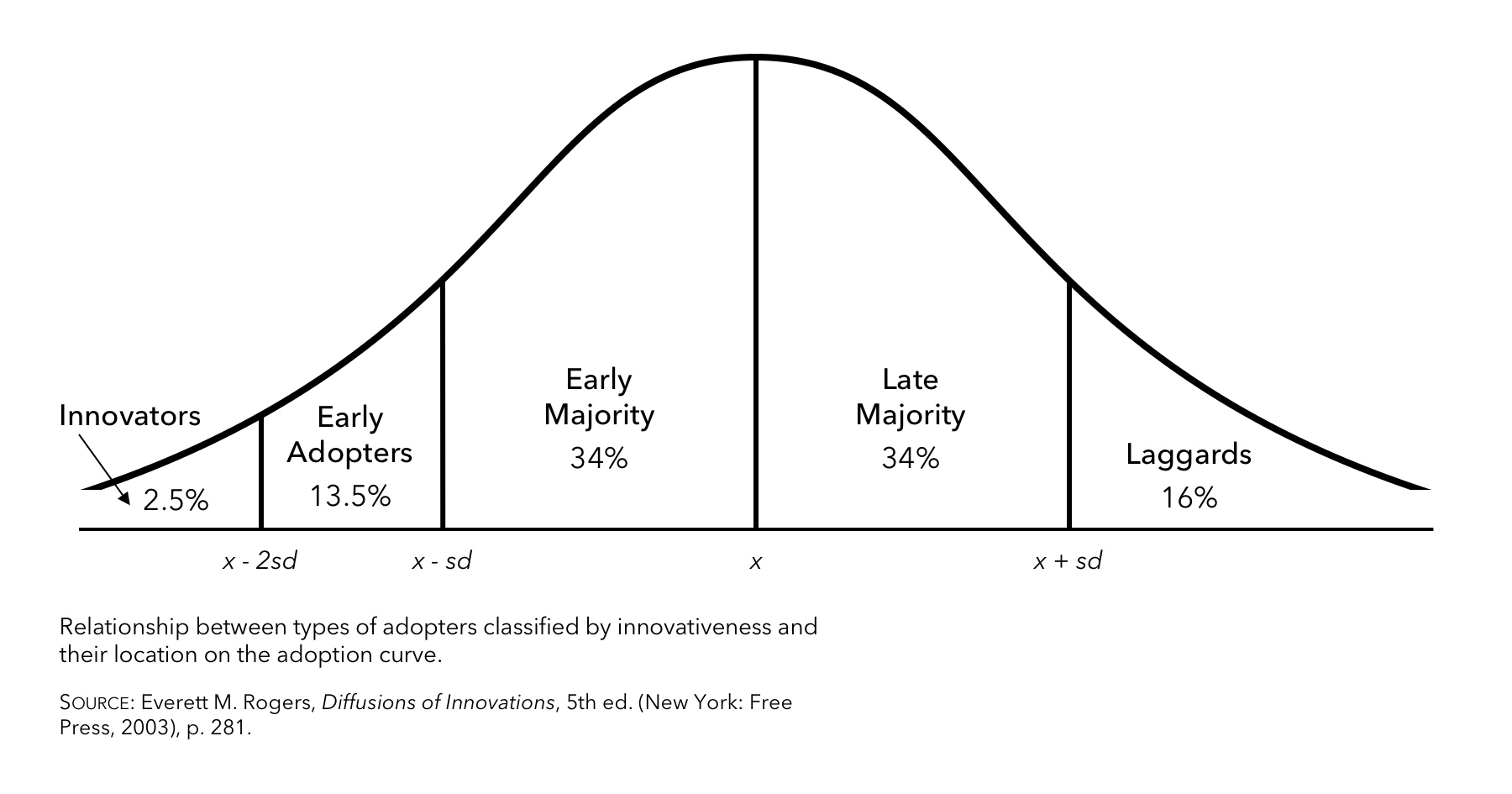

To start, consider focusing on those who are also interested in collaboration– the innovators and early adopters in Roger’s Adoption Curve.

In order to shift a whole organization’s normal mode from interaction to collaboration, adopters eventually need to convince a majority of the organization. Ideally, this process would be maximally inclusive. To create momentum toward full adoption, however, you should combine efforts first with others who are also interested, whether at leadership or grassroots levels.

Next, consider your position in the business. Your methods of influencing should differ depending on your level of influence. Keep reading for tips for leaders, teams, and individuals within an organization.

FOR LEADERSHIP

If you’re part of an organization’s leadership, you have the power to set expectations for your operations around collaboration. This is multi-faceted and includes a few critical steps:

- Ensure your organization has the tools and processes that promote collaboration. This includes commonizing tools between business functions, training that empowers everyone’s base knowledge, and setting up the expectations for how you want to operate.

- Build common values that unite your organization. If everyone has a shared goal but different ideas on the execution of how to achieve that goal, cooperation is inevitable. The values of the organization must provide the guidance. These values must be tied to the personal motivations of individuals as well as the collective.

- Hold everyone accountable for HOW they work. Often, individuals and teams are rewarded for achieving timeline goals and task completion, regardless of compromises that had to be made. This reward practice often negatively affects both the long-term outcome of the project as well as other parts of the organization who are neglected despite doing higher quality work. The type of behavior that your organization is rewarding may reinforce counter-collaborative behavior; for example if someone works all weekend and is treated like a “hero,” but this work actually throws off their integration with others.

FOR TEAMS

Teams should also feel empowered to influence change with a grassroots effort. But there are some things to look out for: grassroots efforts may require some protection if the effort to convert to more collaboration isn’t coming from the top. Sometimes, when teams are viewed as operating “outside the lines,” it can be perceived negatively and could kill any progress early. Ultimately, having team leaders involved and starting with smaller teams or projects can provide proof of concept. Here are three things that teams can start with:

- Challenge your team’s normal operating mode - both in structure and time utilization. Try developing your own team “organizational structure” and laying out people’s strengths to inform it. (Read Gallup’s Strengthsfinder series for more direction.) Or, review your calendar and eliminate ineffective recurring meetings–effective collaboration shouldn’t need as much time in meetings. Reevaluate which participants need to be in which meetings and specifically observe during meetings to assess efficiency and inclusiveness.

- Develop a purpose statement for your team. In lieu of adequate values or purpose from your business, creating your own collective purpose statement connects value to the team’s work and helps in unification. (An idea to try is IDEO’s Purpose Statement.)

- Measure your team’s success. On the outset of the shift to collaboration, consider ways that you might quantify the effects of collaboration. This could be as simple as a “how are you feeling about your work?” type survey across the team. (An idea to try is the Reflect Extension in Microsoft Teams.) Metrics could also be more analytical; look at project lengths, risk discovery and abatement, and novel or patentable idea generation.

FOR INDIVIDUALS

If you’re in a state that may be considered “pre-grassroots,” there are still changes that you can make to impact your sphere of influence and shift towards collaboration.

- Reveal assumptions. During meetings or other opportunities for collaboration, work to identify your and your teammates’ assumptions. During discussions, you can ask “Let’s take a step back, this is my understanding…”, “Is this consistent with your understanding?” Many times, this motivates others to revisit their own assumptions and can lead to a more purpose-driven dialogue.

- Be inclusive in cross-pollinating ideas. Explore opportunities to host peer-review sessions with experts outside of your team to look at an idea or participate in a risk discovery discussion. Specifically call for the input from every individual participating in your meeting. You can lead by example and have higher quality in your own resulting work.

- Experiment with your own organization’s available tools. Often a team isn’t fully utilizing all of the tools it has available. While you may not be able to create a new system for your team, by exploring with tools and systems independently you can become a local “expert” and influence others to consider a change.

In the process of changing from cooperation to collaboration, it’s important to establish expectations. If you’re dreaming of a revolution but don’t have the buy-in, you may end up resenting your team or company or questioning your own abilities. The transformation takes time and work - it’s an evolution - but the work will be motivating and empowering!

Further Reading

Just Sit There. Dec. 23, 2017. Team Health Morale Checks