If you are one of the lucky people who never has too much to do, and who never has to choose between tasks, then congratulations. This blog is not for you.

The Eisenhower matrix is a very simple formalism for making choices.

I am fond of simple formalism - little structures or mechanisms we can use to structure our thinking or our work without too much process, muss, or fuss.

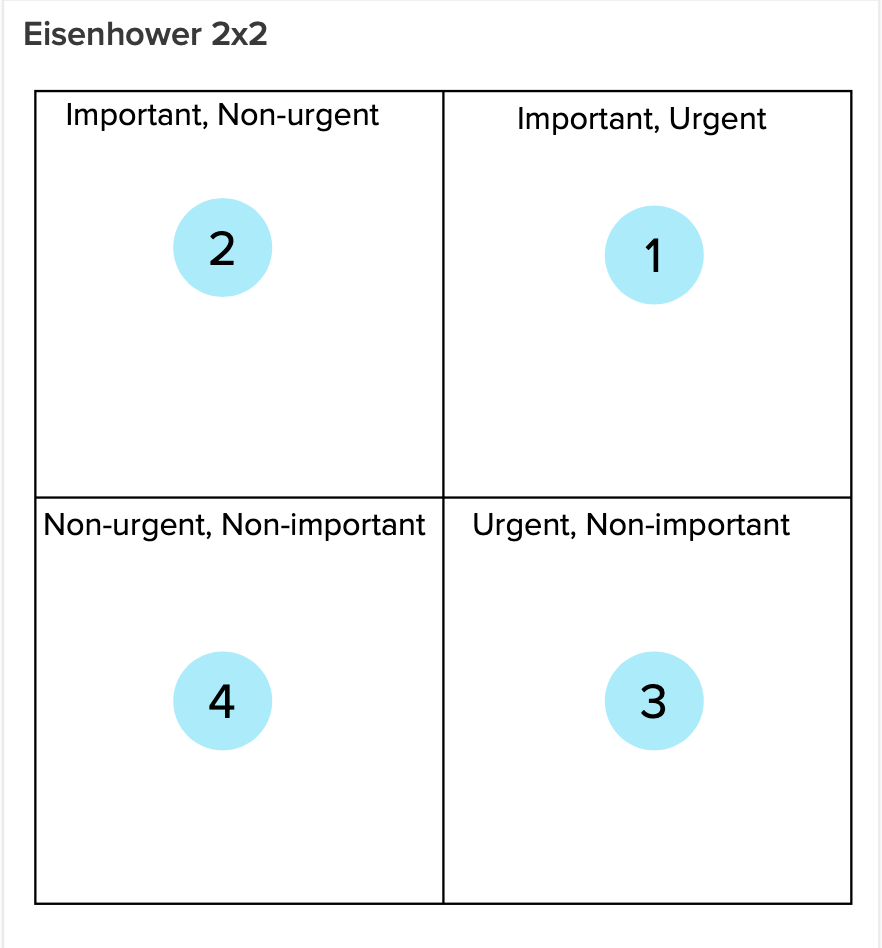

The Eisenhower Matrix looks roughly like this:

On one axis you have urgency, and on the other axis you have importance.

This image expresses absolutes, saying “important” and “non-important” whereas the reality is that most things are in shades of gray.

One must understand x & y axes as gradients, and not see the picture as four boxes into which you can drop things that are absolutely in one of four states.

When we learn to classify tasks according to their importance and urgency, we can begin to handle our workload more responsibly and effectively.

Urgency vs Importance

The first problem people get into with the matrix is understanding the difference between importance and urgency.

You may be surprised to hear that urgency and importance are orthogonal concerns.

If something is important, is it not urgent that we tend to it?

If it is urgent, then isn’t it important that we attend to it right away?

Urgency

Urgency is concerned with immediacy.

Certainly if your hair were on fire, it would be urgent. You would not schedule a meeting about it next Thursday at 11am. To avoid injury, you would quickly take some kind of action, and would follow up with some kind of damage control so that you wouldn’t look as though your hair had been on fire for the next few weeks.

If you spilled cold water on your shirt, there would be a lot of immediacy but ultimately the shirt will dry and water won’t leave a stain – it won’t make any difference in the long run. Later, you may remember it and laugh, but it won’t have a profound impact on your life.

Those are stories of things that are urgent, but not necessarily important.

Often urgent tasks are satisfying because they can be completed in short order.

There is nothing wrong with urgency.

The only time it is a problem is when less-important urgent tasks starve out time for doing more important tasks. One may be caught in the “tyranny of urgent trivia” and miss opportunities for meaningful interactions and personal growth.

A political conversation on social media may be more urgent and emotionally compelling than helping a child with their homework, but you know which of those two activities is going to matter more in the long run.

A friend in trouble is an urgent thing, and likely important to boot.

The opposite of urgent for the purpose of this exercise is deferrable.

Importance

Importance has to do with the long-term impact of a work item.

Will you look back a year, five years, or ten years from now with gratitude that you chose to do this thing?

Will it change the arc of your story, the trajectory of your career, the size of the dent you put in the universe, the success of your company, the wholeness of your family?

Importance takes a long view.

The problem with important things is that it’s easy to defer them when a lot of urgent things are going on.

People get busy and forget to pay bills, maintain relationships, etc.

Your health care (exercise, diet, etc) seems infinitely deferrable when there are interesting and urgent things going on.

Learning can often be deferred. Understanding a relevant technology could change the trajectory of a technician’s career (important), but they could also avoid “wasting time” on such a thing so that they can get their immediate work caught up (urgent).

The opposite of important is transient for the purpose of this exercise.

The Matrix in Time Management

Stephen Covey’s book First Things First explains how to use the Eisenhower matrix to plan one’s day:

- Important + urgent: do these first.

- Important, less urgent: schedule to do these soon

- Less important, urgent: delegate to other people

- Less important, less urgent: don’t do these at all. These items can be sacrificied in order to make time for items with more importance and/or urgency.

This mirrors Dwight Eisenhower’s own use of the matrix.

It may be handy to list things first by importance, and then decide on their urgency.

Many users of the matrix for time management suggest having limits on each quadrant. Have only 5 or only 8 items in each quadrant to avoid overload.

After all, if you have 1000 important, urgent tasks then you are still stuck with too many things to even consider succeeding today.

The Matrix in Feature Selection

Sometimes organizations select product features based on the Eisenhower matrix.

A feature that increases the sellability of a product may be important and urgent early in the product’s life as the team struggles to establish a revenue stream.

Retaining and growing revenue from existing customers may be more important as a business grows, or importance may shift to finding new markets with new products.

It may be urgent to maintain feature parity with a competitor, though it may not really be as important as creating an advantage by introducing new differentiating features.

- Important + urgent: still do these first.

- Important, less urgent: schedule to do these soon, perhaps scheduling some work for proof of concept or product validation right away.

- Less important, urgent: Consider limiting investment in these items, but include them if the cost and risk is sufficiently low.

- Less important, less urgent: Drop these features. If they become important they will resurface. Don’t start planning or designing toward them now.

In software, there is a tendency to call a thing important because you want to get it done. People will rationalize anything if it helps them to achieve their goals. A frank discussion about the importance of a feature to the product community can often help us to get past what we want to call important and focus on what matters in the longer term.

Also, realize that importance and urgency may shuffle over time due to changing market conditions.

- Something that seemed important last year may no longer be important at all.

- Customer validation may show that the urgent new feature we wanted to expedite is not even interesting to users any more.

- A feature that wasn’t very urgent last month might be very urgent as a deadline approaches.

Also, there is some wisdom in limiting the length of the to-do list (backlog). It’s not helpful to have 2000 important, urgent features, because you can work on very few at a time (a developer can do one thing at a time, and many tasks will take more than one developer).

Separating out real importance and urgency from our desire to see our ideas implemented is a difficult job requiring reflection and input from our community, but those who practice it tend to enjoy an advantage over those who don’t.

The Matrix in Learning

When you are faced with a million1 new things to learn and a critical case of Fear Of Missing Out (AKA FOMO), you have the same kind of problem that the Eisenhower matrix was built to solve.

- Important and Urgent: Pick one of these. Focus on it.

- Important but not Urgent: maybe start backgrounding now, pleasure reading, etc. Forgive yourself for deferring it to learn important, urgent things.

- Urgent but non-important: Maybe have someone else tell you, show you, or do the job for you. If you don’t really need the skill, maybe you don’t have to invest too much in it if others are willing to shoulder the load.

- Neither important nor urgent: maybe make bedtime reading of it. Don’t invest.

I’m sure the actual number is much larger. The good news is that everyone only knows a handful of the available things to know, so we’re all in this together.

The interesting thing about this exercise is something I call “clearing the board.” Once you’ve learned some important topic to your immediate need/satisfaction, don’t automatically promote the next item in the list. Throw the list away and start over. You probably don’t want to be studying the things that seemed important to you 6 months ago.

The world is super-fast-moving, and the amount of activity inside our heads can’t compete with the activity in the rest of the world. Plan to adjust your learning plans as your context and roles evolve.

The Matrix in Training

One painful mistake corporate trainers sometimes make is to want to express the many things that they know, rather than the relatively few things that students need to learn well in order to do great work.

Since we measure effectiveness2 of training based on student’s learning, not on teacher’s exposition or entertainment value, we need to focus on what students most need.

- Important and Urgent: Things a student will need to apply immediately in order to handle the subject competently at all.

- Important but not Urgent: Things that a student will need to understand as they progress in order to solve problems they will inevitably encounter

- Urgent but non-important: Hot topics, controversies, debates, developing trends. Any of these may not pan out or matter in the long run. Minimize these, but add them in if you find yourself with copious free time.

- Neither important nor urgent: Leave these for some other source, possibly social media or stack overflow to teach.

Typically we run out of time in training rather than running out of material. If we focus on the most-important and most-urgent topics, we’ll give students the best chance of handling topics. We often don’t have much time for important, non-urgent bits.

While this clearly plays into lesson planning, it also plays into delivery. We may plan to “squeeze it all in” and overwhelm students. It’s better for us to divide work into sections and manage our time by adding the most important, urgent slices that the timeframe allows us.

Other Uses?

We hope that you will find other uses for the Eisenhower matrix, wherever you may have other decisions to make.

Are there situations in which the matrix doesn’t work well?

Are there crucial decisions where the matrix is not applicable?

Feel free to contribute your ideas and experiences in the comments.