Large changes are hard.

Hard enough that they seldom happen, outside the context of a crisis.

What if changing wasn’t a traumatic event but a lightweight, continuous process?

One Percent

Sir Dave Brailsford is (as of this writing) the Director for Great Britain’s pro cycling team, “Team Sky,” and he famously promoted a concept called “aggregation of marginal gains.”

He believed that if you could improve everything about cycling by only one percent, then those gains would compound together and create a tremendous, game-changing difference.

Team Sky went from “the team nobody expected to win” to having what some call “the most successful run in modern cycling history.”

While some may argue with how scientific or nonscientific his methods are, or whether his success was really single-cause, most people associate the team’s success with their unrelenting search for small improvements .

Mindless Margins

A similar concept is presented in Brian Wansink’s book, Mindless Eating

His group has conducted many experiments into how and why and how much we eat.

Lansink found that we really don’t pay as much attention to portions as we think we do, such that serving food in a larger dish or providing distractions (such as a movie) will fool people into eating perhaps 30% more food than they intended.

Such changes abide in what he calls the “mindless margin.”

The good news about the mindless margin is that we can use it to our advantage.

By doing simple things such as putting healthy snacks out on the counter instead of chips, buying smaller cups and plates, and not eating in front of the television we can leverage our inattentive eating habits and thereby perhaps control our body weight.

By making small, intentional changes to our environment and habits we may find ourselves mindlessly eating less or eating differently.

“The best diet,” he says, “is the one that you don’t know you are on.”

Two Seconds

Paul Akers, the author of Two Second Lean, is a huge proponent of the Lean principle of Kaizen (continuous improvement).

He reports “Toyota still makes millions of improvements worldwide to their processes and they have been thinking Lean for over 50 years.”

In one short video, he shows how his marginal gains from shaving mere seconds off a 45-second process saves his company approximately 200 person-hours a year.

As one watches this video, it initially seems like the team is paying undue attention to such a small matter. As the operation is easily trimmed from 45 seconds to only 30 the viewer has an urge to declare completion and move on, but the video continues. Eventually, we see the operation reduced to only 15 seconds – one-third of the initial time.

Akers does not usually perform such a large, focused revamping of a process.

When an improvement is a big event, team members struggle to find a large block of uninterrupted time to implement the improvement.

Paul Akers has learned a simple trick to make improvement continual: he asks every employee to identify and implement one change which will save them a mere 2 seconds a day.

Each team member is asked to make only one such improvement but is expected to demo a new improvement each day.

Impatience

My friend and colleague Woody Zuill is a pioneer in Mob Programming.

In mob programming, an entire team works on one problem, all at one time, all together, on one computer.

It is an approach which he and the team at Hunter Industries believe gave them huge performance increases and cost savings.

Most people would expect that such an approach would lead to a slow-down and a huge cost increase for all features.

One of the reasons Mob Programming produced such surprising efficiency is that people in large groups will not tolerate constant small inconveniences.

Instead, impatience drives the team to find safe shortcuts.

“It is powerfully revealing when an entire team experiences waste. Minor annoyances and delays are quickly exposed and dealt with which provides a streamlined path to improvement” says Zuill.

Rather than tolerate “just a few minutes” of copy-paste-edit work, the team will create templates or macros.

Rather than repeat a complex series of mouse operations, the team will find keyboard shortcuts or build script files.

Routine, dull, tedious work that we would happily “gut through” when working alone becomes visible as it wastes the time of a whole team.

Furthermore, Zuill notes that as the team focuses on its work together and efficiencies so-gained, many larger problems and inefficiencies seem to simply fade away.

Worth It?

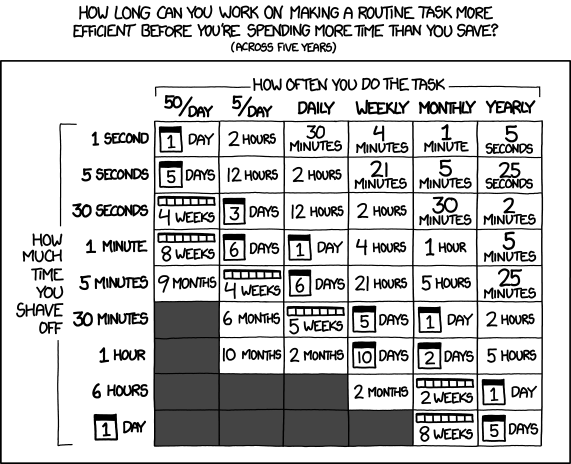

In 2013, Randall Munroe produced a table to help people visualize the value of small changes.

Trivial Changes

While big changes are frightful and can be expensive, it’s relatively easy to make small changes every day.

- Merely renaming a variable or extracting a method can improve readability, saving each person who edits the same code a few seconds every time they visit that file.

- We can cut two kinds of waste out of meetings by velcro-ing markers to the side of a whiteboard and moving all permanent markers at least a meter away from the nearest whiteboard.

- A few simple scripts or shell functions save me minutes per hour nearly every day.

- When I was using TMUX for pair programming, I kept a cheat sheet stuck to my wall in easy view. That saved me several minutes per day.

- Using an auto-tester such as Python’s sniffer or PyCharm’s auto-run toggle means that I always have a fresh test run when doing TDD.

- I put my .vimrc file on the internet so that I could download it whenever I provision a new machine or VM, saving me time as I no longer have to recall and type my settings.

Continuously learning and experimenting is one of the four pillars of Modern Agile.

Whether you are practicing XP, Kanban, scrum, or even waterfall processes, we believe continual improvement is crucial to building powerful teams.

Have you been making small changes? Please share some of your stories (or links to them) in the comments below.