Look at these “user stories” I recently encountered:

As a developer, I want to refactor the BarSplat module so that it has less duplication

As a developer, I want to configure Jenkins so that we have continuous integration

As a product owner, I want to have the stories estimated so that we can make a good plan

As a tester, I want the test cases defined so I can test the system

In Planning Extreme Programming, Kent Beck and Martin Fowler described a user story as “a chunk of functionality that is of value to the customer.”

Where is the customer value in those stories?

Note: My argument is not that those activities are not good or important things to do (they are for this team), but that thinking of them as user stories misleads the team and its customers.

Writing something in the form of a user story when it's not about users of the system misses the point.

The Connextra Style of User Stories

One popular format for user stories, prominent in Mike Cohn’s book User Stories Applied, is a template originally developed at Connextra years ago:

As a [role], I want to [do something]so that [reason/benefit]

The above stories fit the template, but the roles are about the creators of the system, not its users.

Users of a system don’t care about the problems of the system’s creators; such stories are not Valuable to them (in the sense of the INVEST model for user stories).

Where Do Poor Stories Come From?

“Stories” addressing the creators of the system seem to have several sources:

- Useful high-level stories (aka epics) that the team has split in a technical way rather than a user-focused way. The team divided them by how (technical tasks) or who will implement them (creator roles). (Splitting stories is a good tool, but splits work best when they take a customer’s point of view.)

- Cargo-cult splitting: The team may have heard that stories should be smaller than a sprint, or a week, or a day, but the team doesn’t really understand why or how. So they fall back to doing what they’ve always done: dividing features into technical tasks.

- “Busyness accounting”: Tim Ottinger notes that some teams have become focused on the desire to claim velocity “credit” for any activity. In effect, they’re counting effort rather than results.

- Tools: The tools we use (mental or electronic) can push us in the direction of just calling everything a story. This sloppiness can lead to a muddled view of the project’s real state.

Tasks Are (Necessary) Waste

Lean thinking distinguishes between value and waste: value is what the customer wants, and anything else is waste.

From that perspective, many of the activities teams do can be regarded as a type of waste, but we don’t know how to develop software effectively without doing them.

Lean teams talk about this kind of waste as “Non-Value-Added But Necessary”: work we do because we have to.

Consider this conversation:

Customer: How long will it take to add feature xyz?

Programmer: Five days, including a day to refactor the frobble, and a day to test.

Customer: Then let’s skip the refactoring and testing, and call it three days.

Programmer: No, if we skip those it will end up taking us even longer.

Even in this short dialog, we can see that the customer isn’t confused: they just want their feature, as soon as possible. Customers value tasks instrumentally, as required steps on the way to getting what they really want.

It’s not fun to think of what we do as waste, and this is not a call to skip doing the tasks that we need to develop software effectively.

Remember the “But Necessary” part: these activities might go away in a better world, but we still have to do them in this world.

We have to do technical tasks for our projects, but let’s report progress in terms of value: delivering what customers want.

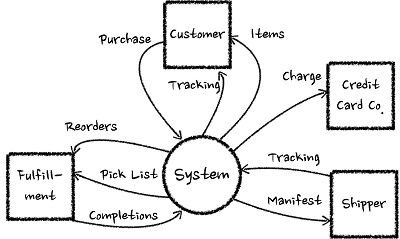

Tool: Context Diagrams

One tool we use to keep our stories honest is an old one: the context diagram. It shows the system in the middle, and the users or systems it communicates with around the edges.

The goal of a system is to affect things outside the system.

Real stories go from outside the system boundary to inside the system, or vice versa.

If we see a story focused only on things happening inside the system, it’s a sign that this is an implementation detail, not something the user regards as a system behavior.

Tool: The Role-Action-Context Template

We also default to a different template to write the headline of a story: Role-Action-Context.

| Role | Something or someone that sends a stimulus into the system boundary |

|---|---|

| Action | How the role triggers the stimulus; usually verb+object |

| Context | Optional: where or when the action applies |

For example, the story “Buyer purchases items using credit card” tells us who is using the system—the buyer, what they’re doing—purchasing items, and (optionally) in what context or approach they’re doing it —using a credit card.

This template helps reduce the problem of tasks masquerading as stories, and keeps stories focused on accomplishing something for a user of the system.

So What Should We Do?

First, look suspiciously at any story whose role sounds like a person involved in development, rather than a user (human, hardware, or another system) that interacts with the software at runtime.

Second, see if any of those tasks can be framed as a functional behavior or a quality characteristic of the running system; if so, rephrase them.

Tasks are for the development team.

Focus on stories as progress, not tasks.

Finally, recognize that your team will sometimes just have tasks. You may decide to track tasks internally, but don’t treat them or track them as direct progress on the developed system.

Let’s write stories that provide direct benefits to our users and customers!

If you want to learn to write great user stories, check out our eLearning course “Composing User Stories”.