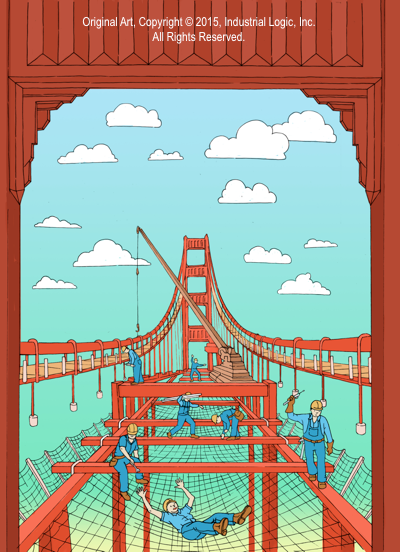

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression in the United States, building bridges was a dangerous job. 24 workers died during the 1933-36 construction of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. One Bay Bridge engineer recalled,

"The worst aspect was not being able to show any fear. Those steelworkers were merciless, and to preserve our self respect we had to act nonchalant and follow along, walking those beams and planks, climbing through small holes and hanging by our teeth even though our clothes were drenched with cold sweat."

Today’s high-steel construction workers have no such fear since safety is an integral part of their work. While we expect zero deaths and few-to-no injuries on today’s projects, back then, accidents happened frequently and the grim expectation was that 1 life would be lost for every million dollars spent.

And that is why the Golden Gate Bridge is so remarkable. Built around the same time as the Bay Bridge, it operated more like a modern construction site in its devotion to safety.

Joseph Strauss, chief architect for the bridge, said "We had the idea we could cheat death by providing every known safety device for workers."

During 44 of the 51 months of construction, there were 0 deaths and few injuries. Strauss used the latest safety equipment, invented new safety equipment and made safety procedures mandatory.

Since errant flying objects, like falling rivets, frequently injured workers, Strauss partnered with a company to adapt mining helmets for bridge construction. The bridge’s resident engineer, Russell Cone, supervised safety for all workers and made the Golden Gate construction site the first mandatory hardhat zone.

Strauss gave workers glare-free goggles to protect them against going “snow blind” from the sun reflecting against the water and he supplied special cream to protect workers skin from wind burn. He even co-developed and provided innovative respirators for steel-cleaning workers to protect them from inhaling hazardous materials.

In restricted movement areas, where high winds and slippery surfaces could easily cause accidents or death, Strauss made it mandatory for everyone to wear safety belts with “tie off” lines. And in case of an injury, he built a field hospital beside the construction site and staffed it with doctors.

If anyone was caught not wearing critical safety gear or following safe protocol, he could be dismissed on the spot. One gruff steel worker was fired immediately when he refused to attach his safety belt to a tie-off line.

When it came time to begin construction of the bridge’s roadway, Strauss envisioned the most “expensive, elaborate safety device ever conceived for a major construction site.” It was a safety net that would go underneath the emerging roadway. At $130,000 dollars, it was a precious sum in the midst of the Great Depression. Strauss lobbied hard and won its approval.

The safety net grew as the roadway grew, extending 10 feet beyond the width of the roadway to protect workers at all times. Morale on the construction site was boosted by this safety net. One worker said, “No matter how high up you were and how hard you’d been blown off, you would still fall into the net.”

Nineteen men accidentally tumbled into the net, each cheating death. They called themselves the Halfway-to-Hell club.

One historian said in this video,

"The loss of life, the delays that would occur from men working slower because they had to be a bit more careful so they wouldn't fall, probably made the $130,000 dollars a very economic innovation."

The excellent safety record was shattered during the final seven months of construction. One worker was crushed by a support beam in October, 1936. And on February 16, 1937, a five-ton platform collapsed, ripping through the net and sending 12 men plummeting 220 feet into the frigid waters below. Ten of those 12 workers died from the fall, bringing the total fatality count to 11.

Without the safety net, that fatality count would have been 30, since all 19 members of the Halfway-to-Hell club would have also perished. Given it’s $35 million dollar budget, 30 deaths during construction would have been close to the 1930s average of 1 death for every million dollars spent.

Yet injuries and deaths were kept to a minimum during construction of the Golden Gate Bridge because safety equipment, safety training, procedures and oversight were an integral part of the work. It resembled a modern construction site at a time when little attention was paid to safety. Today, the bridge is both an iconic symbol of the San Francisco Bay Area and a landmark for worker safety.